I’ve been having the conversation a lot lately. You know. The conversation about young adult books and why it’s important, at least to me, that they be actually written with a young adult audience in mind. I’ve been talking to a lot of readers about why the heroine of Blood To Blood, Angel Brown, doesn’t swear and, at the age of sixteen, is still a virgin.

We’ve all heard, ad nauseam, about how the young adult book market is growing by leaps and bounds. But any fan of YA literature, and classics such as Little Women, Lord of the Flies, or The Hobbit (one of the biggest fans would be me) can tell you it’s not a new thing, it’s not a trend and YA is here to stay.

But one relatively new, and glaring, aspect of YA book readership is the fact that the majority of consumers, specifically of the YA fantasy genre, is way older than the age defined as YA audience. Seemingly, the average reader is a Kindle or Nook-toting 30-something year old mom with 1.37 kids and that audience age can go as high as the 50s and beyond.

Fully 55% of buyers of works that publishers designate for kids aged 12 to 17 – nicknamed YA books — are 18 or older, with the largest segment aged 30 to 44 – Bowker

Part of this phenomenon, well-documented with the Twilight series, seems rooted in the fact that women of all ages love a good story involving the blossoming of the heart. Moms love to relive the fluttery feelings they had for hot guys when they were still young and it all seemed so exciting and over-the-top. I myself got hooked on Twilight right as my marriage was falling apart and lost myself in memories of those feelings that I once had and missed terribly.

So there’s nothing wrong with old-ass women such as myself writing and reading YA books, but what happens when something labeled and marketed to a young adult is geared towards said old-ass women?

There are a number of YA series out there that depict their teen heroines as potty-mouthed, sexually adventurous, fashion-plate, overly made-up biatches alá 80s/90s music videos. As if said old-assed women want to somehow go back in time to re-invent themselves as vampire huntresses, immortals or simply the most popular, hottest chick in school. At what point do we take responsibility for shaping how young adults see themselves and relate to the world? What happens when every other sentence features an expletive? Seriously, why not utilize more adjectives; overused swear words, like many love-lives, get old and boring quick.

Why Angel Brown Doesn’t Swear

Take an example from ultra-violent Clockwork Orange, the 1963 classic featuring raging, raping, killing teens and a society out of control. As dark as the subject matter of this once-banned book gets, the author Anthony Burgess didn’t use swear words as a crutch or carrot, and instead developed the characters and their world through the use of unique language which, in turn, offers an expanded view into the underlying themes.

Am I a saint? Hell, no. My book’s only in pre-release right now, and already it’s gotten criticized for depicting earth craft (sometimes called witchcraft) and blood rituals. But, I feel strongly about young girls who read my books coming away from them without the feeling that it’s somehow ok to lower your standards of personal civility and self respect in order to be, or be perceived as, sexy. Preachy, maybe. Everyone’s cup of tea? Certainly, not. But that’s why Angel, with all her amazing powers, is as straight-laced and conservative as any character I’ve ever written.

At the end of the day, I believe authors have a responsibility to their audience. As responsible adults it’s up to us to decide whether what we’re writing is truly for young adults or for the unrequited fantasies lurking within our own grown-up subconscious.

Why Angel Brown Doesn’t Swear

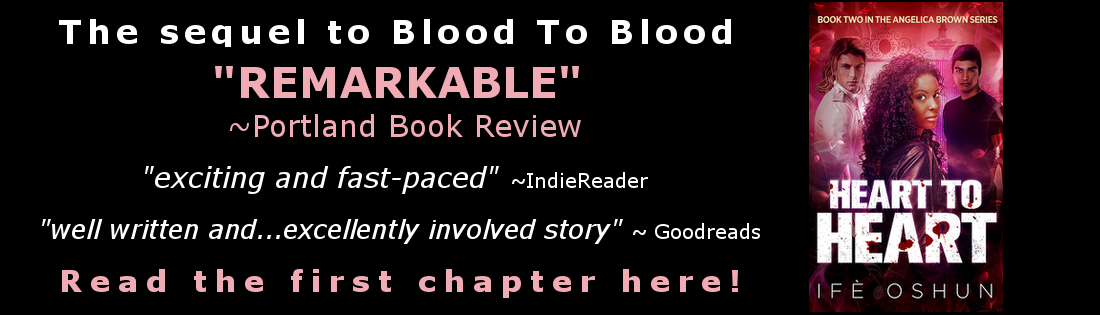

November 7, 2014: Edited with the Heart To Heart cover